Filmmaking Case Study: How to Tell a Meaningful Story in Under 3 Minutes

Sometimes the most emotionally-complex films come in the smallest packages.

Last week, I wrote an article about the incredible benefits of making micro-short films. Chief among those benefits: getting really good at the craft of filmmaking, finding your unique artistic voice, and building an audience.

What I didn’t have in that article, however, were examples of micro-short films done well. So that’s what we’re going to focus on today — one compelling micro-short and the story of why and how it was made.

The film comes from Brenton Oechsle, an independent filmmaker based out of Indianapolis. It’s called Undertaker, and despite its 2:30 running time, it’s a nuanced exploration of grief, memory, and hope.

So without any further ado, here's Undertaker.

Looking closely at the script of Undertaker

With films like these, it can be extremely helpful to delve into their scripts to see how they're working on a more foundational level. In this case, Brenton was kind enough to send over the script for Undertaker, so I've included it in its entirety below.

INT. MORGUE

Silence except for the incessant buzz of fluorescent bulbs.

The hands of an undertaker button the recently pressed shirt of a dead man.

He slowly makes his way up to the man’s tie which he straightens.

After doing so, he methodically cuts the man’s finger nails before placing his hands across one another on his chest.

The undertaker stops to admire his work with nothing more than a blank expression.

He is younger than expected. Mid 20s. Neat and trim.

CUT TO:

INT. DINING ROOM, EVENING

The undertaker slices into a flank steak with his silver knife and fork. He stares at his meat in silence.

GUEST

You ever just have a memory pop into your head out of nowhere?

The undertaker looks up towards his guest sitting at the opposite end of the dining table.

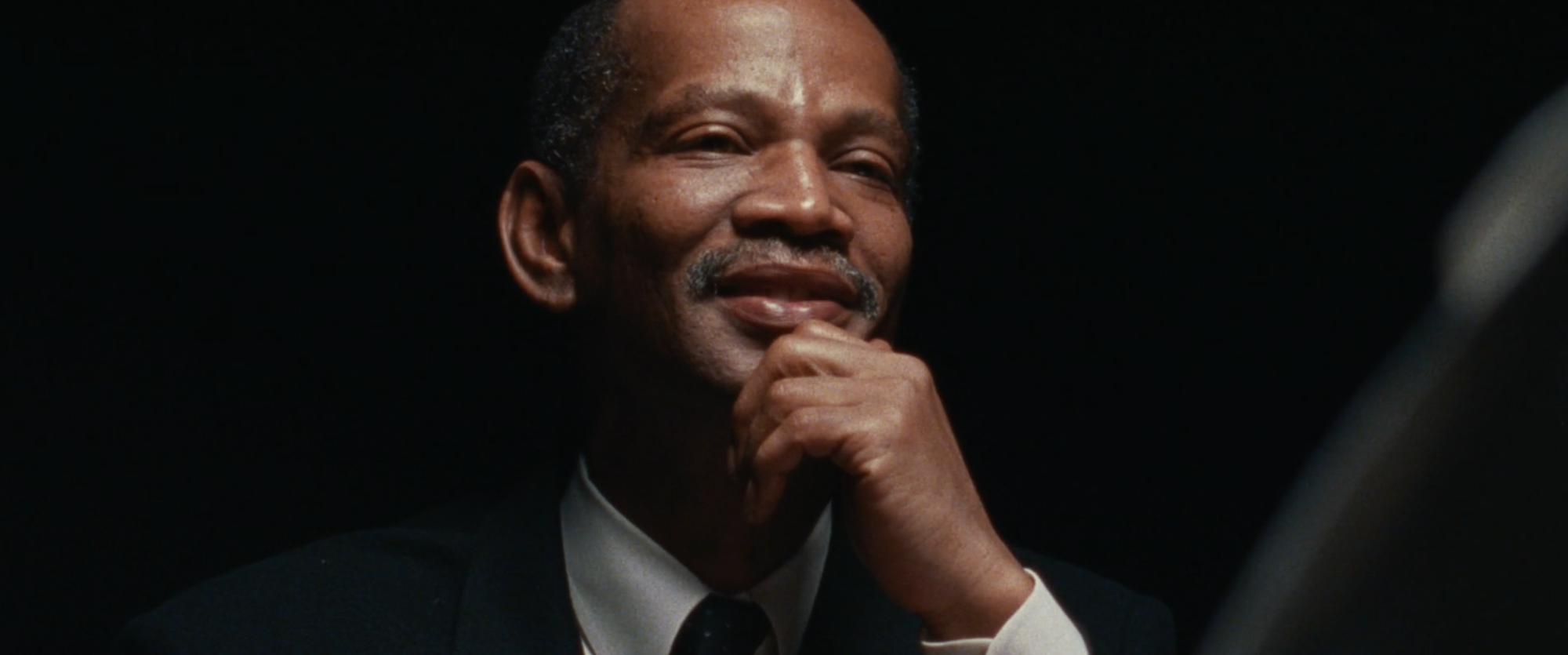

The guest is in his late 50’s, well dressed and displaying kind features.

GUEST (CONT’D)

For some reason it was from when you were real young...

The undertaker pauses in anticipation of his guest.

GUEST (CONT’D)

Mom had just passed...

The guest breaks eye contact and looks away.

GUEST (CONT’D)

You kept looking out the window... like she was gonna drive up any moment.

The undertaker drops his head to focus once more on his meal.

GUEST (CONT’D)

You were so confident.

The guest smiles.

GUEST (CONT’D)

Gave me hope she might just walk through the door.

The guest looks down and the undertaker pauses from eating.

GUEST (CONT’D)

I don’t know… I guess maybe you needed to hear that.

The undertaker smiles slightly.

CUT TO:

INT. MORGUE, LATER

The undertaker enters and flips a light switch. Intermittently the fluorescents buzz to life.

He approaches the man on the table.

For a moment he stands there, his gaze fixed on the face of his late father.

FADE TO BLACK.

Interpreting a script that seems simple, but is deeply nuanced and emotionally challenging

As you can see, the script itself is incredibly simple, stripped down to the bare essentials in terms of action and dialogue. But let's break down what's actually happening here, because it's more complex than it appears on the surface.

We've got three scenes. The first one introduces the audience to the undertaker. It shows this character doing prideful, detailed work. It's important to note that there's nothing particularly meaningful about this scene yet because the context comes later.

Then we cut abruptly to a short sequence that represents a memory, or perhaps it's the undertaker's internal dialogue. Either way, this sequence connects the first and last scenes in a profound way. It's the glue that holds everything together and provides the emotional core of the piece.

In one sparse monologue, the guest, who we quickly learn is the undertaker's father, shares a small story, a sad but beautiful memory. It's all about using seemingly insignificant moments to find hope in the darkest of times. It's all about this idea that the deceased live on in the hearts of the people who loved them the most.

Then with a poignant, vaguely mysterious remark at the end of that monologue — "I don't know... I guess you needed to hear that" — we're set up for the realization in the final scene.

After cutting back to the morgue, we find out that the undertaker has been working on his father, and this realization brings an entirely new meaning to the first two scenes.

The detailed, prideful work from the first scene becomes far more than an undertaker just performing his job duties. It becomes imbued with both a sense of deep respect and an overwhelming sadness.

The memory scene becomes a momentary reprieve from that sadness, where the undertaker is able to use his father's simple story of hope as exactly that. This scene represents hope in a very tangible, meaningful way.

What's crazy is that all of that nuance and emotional complexity comes from a story that takes up roughly two minutes of screen time.

That's the power of iceberg storytelling. Very little of this subtext has to be spelled out because the audience is given just enough information to be able to explore those emotional complexities on their own.

As filmmakers focused on creating micro-short films, that's an incredible tool that we have at our disposal. We can purposefully scratch at the surface of these larger stories and themes, then let the audience bring their own histories and emotional tendencies to the table.

An in-depth interview with Brenton Oechsle, writer and director of Undertaker

I had the chance to chat with Brenton and dig deep into why he made this film, how he made it, and to get his thoughts on the nature of micro-short films in general. This interview has been edited from its original format for structure and clarity.

Filmmaker's Process: Give us a bit of background on yourself as a filmmaker. How did you come into filmmaking and how have you pursued it throughout your life?

Brenton Oechsle: I got my start in middle school like many filmmakers do, hanging out with friends and messing around with a camera making movies.

One of the earliest truths I learned was that the outcome of your work largely depended upon the people you surround yourself with. So throughout high school and college, I was constantly on the lookout for collaborators while at the same time soaking up as much knowledge about filmmaking as I could.

It wasn’t until after college that I was blessed to meet and work with my two greatest collaborators to date, Kassim Norris and Skyler Lawson. The time and circumstances in which we all met could not be described as anything less than divine appointment.

Together we formed our production company 5AM Films, through which we continue to produce narrative content. I believe strongly that you don’t have to move to a big city to pursue a career in filmmaking, because often times, the people who you are going to work best with and with whom you will create your best work can be found in your own backyard.

FP: Why is it important to you to keep making films?

Brenton: When I was in college, my mentor gifted me with Andrei Tarkovsky’s book Sculpting in Time. Through this book I learned that not only was Tarkovsky a brilliant filmmaker, but he was also a man of considerable faith.

“The aim of art is to prepare a man for death, to plough and harrow his soul, rendering it capable of turning to good.”

More than anything, his faith had the biggest influence upon his work. His concept of unity between faith and cinema resonated deeply with what I had held in my heart for years and it served as a confirmation for me that filmmaking was the right path for my life.

The goal of my work and my drive to continue making films can be summed up no easier than through one of the greatest quotes in the book, “The aim of art is to prepare a man for death, to plough and harrow his soul, rendering it capable of turning to good.”

Much like Tarkovsky, my work is driven by my faith and through a desire to stir empathy within an audience.

FP: Why was the micro-short format the right choice for this project specifically? It’s both thematically and emotionally complex in a lot of ways, so why did you opt for the short running time?

Brenton: Largely due to my cinematographer, Kassim, I had been rather obsessed with the possibility of being able to tell an entire story in a matter of minutes.

Since everything I had accomplished up until that point was based in the long form — in the past I made a novella-film that was supposed to be a short and then I made a short that was supposed to be a feature — making something so short was attractive to me and I wanted to prove to myself that I could do it.

“Trying to capture such a complex emotion in a short period of time meant that I had to simplify everything. Not just simplify the means of communication through a narrative, but also simplify the very nature of what I had come to know about filmmaking.

It was almost as if I was throwing out everything I had learned and started from scratch. This process of starting from scratch may have been the most beneficial experience of my career to date.”

Of course, the subject of death is something that has been focused upon in every art form since the dawn of man, but trying to capture such a complex emotion in a short period of time meant that I had to simplify everything. Not just simplify the means of communication through a narrative, but also simplify the very nature of what I had come to know about filmmaking.

It was almost as if I was throwing out everything I had learned and started from scratch. This process of starting from scratch may have been the most beneficial experience of my career to date, and I think it is a process that is too often forsaken in favor of the tried and true.

FP: When you’re working with such a short amount of screen time, the rules of screenwriting and storytelling change drastically. How do you come up with and refine a story so that it works in the micro-short format?

Brenton: There is something beautiful about the nature of restraint. You’ve heard the saying that "less is more." Well, I believe this to be especially the case when it comes to filmmaking.

The shorter a film is, the less time there is to get the point across. But more importantly, the less time there is for the audience to care. If you think of a feature film as a paragraph, and a short film as a sentence, then I look at the micro-short as a fragment.

So in effect, the very first impression that the audience has of a character in such a compressed period of time will make or break the film. For a micro-short to be effective, I believe it needs to be extremely visceral, it needs to attack the audience on a gut level.

I would also liken the micro-short to the effectiveness of a joke, which are often short and end with a punchline, leaving its audience satisfied. The best jokes in my mind are the ones that are simple, ones that you don’t have to think about but leave you smiling regardless. The micro-short will be the most effective when its story thrives off the simplest of ideas, which is honestly why a grand majority of micro-shorts are biased towards comedy.

“The very first impression that the audience has of a character in such a compressed period of time will make or break the film. For a micro-short to be effective, I believe it needs to be extremely visceral, it needs to attack the audience on a gut level.”

Also, I think it is paramount that when approaching the inherently simplistic form of the micro short, a storyteller needs to open their eyes to the beauty that can be contained in a moment. These moments that I am talking about happen around us constantly, but most of them go sadly unnoticed.

Now if you find yourself perplexed and don't quite know how to go about recognizing these moments, I suggest you go spend some time people watching. It doesn't matter where or when, although the more crowded the space the better, just as long as you are observing humanity and how people interact with one another. Do this regularly enough and eventually you will have at least one moment in which to build a micro short around.

I think as filmmakers and artists, sometimes we have the tendency to bite off more than we can chew, so the most important function of the micro-short is that it forces you to make rules for yourself based on the resources and funds that you have available to you.

A tip I learned from my good friend is to create an inventory of the assets you have available to you at the moment in which you could use for any future projects. This includes everything from possible cast and crew to available locations. This comes in very handy once you have stumbled upon a concept and you can resort back to this inventory.

FP: Walk us through the process of making Undertaker. Where did the idea come from? How did you go about writing it? Is there anything significant about the production and post you’d like to share?

Brenton: As the path of an artist who seeks many ideas out, it is usually the ones that find me which end up becoming something of worth.

Unfortunately this idea found me through a very dark period in my life. Last fall, my cousin passed away in a manner that was all too sudden and a lifetime too soon. His was my first real death that I had to face, and it had me questioning a lot of things.

After I got the news, I was walking around because I just couldn’t bear to sit still, and then the sight of seeing people dancing and laughing across the street made me sick. I could not and still cannot fathom how in one instant a single person’s life can reach its very bottom while the person next to them carries on without a worry in the world. I wished I could somehow give a shred of hope to those at their bottom.

Naturally, my first recourse was to stick these feelings into a film. In the past, it has seemed that my ideas for a narrative have been so vast that structuring them into the format of a short film felt like chopping an epic novel down to a three page pamphlet which would be handed out at grocery stores. So using the springboard of death as my introduction into the micro-short was the perfect exercise for me.

“I think as filmmakers and artists, sometimes we have the tendency to bite off more than we can chew. I think the most important function of the micro-short is that it forces you to make rules for yourself based on the resources and funds that you have available to you.”

As life would have it, around that time was when I ran into an old classmate who told me that he was studying to become a mortician’s assistant. It was this interaction that made me wonder if morticians are ever haunted by their subjects. This sent me down a path in which I eventually came up with the framework for this film.

I knew I wanted two characters, a mortician and the man he was working upon, someone preferably close to him. Then I knew that in some way I wanted the man to impart some sort of hope to the mortician.

As I am a huge fan of filmmakers such as Mike Leigh and John Cassavetes, my first idea was to do this through dialogue, as it would be easier to accomplish than through simple action.

Of course, as the limits of the micro-short were imposed upon me, I knew the interaction had to be short. So what I settled on was the imparting of a simple memory, which apart from the context it’s in, means nothing, but in this scenario is the character’s whole world. From there it was a pretty systematic process of figuring out the beginning and ending action of the mortician working on the man, and the interaction between them stuck in the middle.

I decided to shoot this film on 16mm because there was something very relevant to me about shooting a project about hope and death on a tangible medium that has been dying for so long, but the hope for its sustenance has never been more prominent.

“I think the most important function of the micro-short is that it forces you to make rules for yourself based on the resources and funds that you have available to you.”

As I discussed running time before, I will reiterate that a story only takes as long as it needs to in order to get its point across. If it’s too long, the audience will get bored. If it’s too short, the audience will fall into confusion. So my effort was to hit it right on the money with this one. Usually my scripts end up playing out about 1.5 times longer than the page count, so I planned the 2 page script to end up somewhere in the ballpark of 4 minutes. I ended up with 2.5. Running time can be a very elusive mistress to please.

For some reason my concepts have always taken longer for me to execute than others, so from conception to conclusion even this idea took me several months. With every new project I think I’m learning to be less particular about the details that end up dragging out the process longer than it should.

FP: Do you plan to keep making micro-short films now that you’ve released Undertaker? What’s next for you and the team at 5AM Films?

Brenton: I definitely plan to continue making micro-shorts in the future. Especially for the fact that since the projects are so short, they are quite financially viable to shoot on film. Lately we have been talking about doing a darkly comedic micro-short on B&W 16mm.

FP: Anything else you'd like to add about micro-short films?

Brenton: I recently read that in the last 16 years the attention span of a human has fallen from 12 seconds down to 8 seconds. The attention span of a goldfish is 9 seconds. While this is unfortunate for filmmakers as a whole, I think it is great news for those creating micro-shorts. And with that, my greatest advice to go out and try one! If it’s no good then try again!

FP: Where can people find you online to stay up to date with your latest work?

Brenton: The rest of my work can be viewed on my Vimeo, portfolio website, and through my Instagram where I have recently been posting 35mm stills.